He had never been the only person in a train car before. He noticed that the ride was bumpier when the train was not packed with a rush hour crowd. The rhythmic rocking of the train made it easy for him to think about nothing. Thinking about nothing was not worrying. He was not worrying if moving to the city by himself had been a mistake. He was not worrying about getting mugged on the walk between the train stop and his apartment. Most importantly, he was not worrying about what would happen when he got back to his apartment at two o'clock in the morning with no keys.

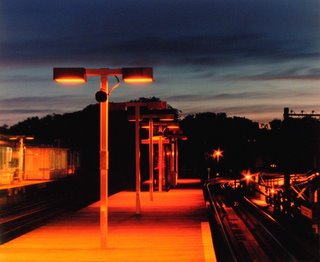

Only when the train had reached the end of its line, far beyond his stop, did he become aware again. Stoic, he crossed the platform, and, even though he knew it would be at least twenty minutes, he waited patiently for a train in the opposite direction.

A few minutes of waiting in the silence with nothing to distract him, and he was back to the worrying that had perforated his entire day. It started with the memory of a feeling. He was there again, standing in the chilly foyer, waiting for the superintendent to let him in. That was the most humiliating part of the memory. Worse than the image of her in a dirty lavender bathrobe pressing her lips together in general disapproval of his existence. Worse than remembering that she had made him wait outside her door as she looked for her copy of his lease. Even worse than when she made him read aloud the section that said the superintendent had the right to charge ten dollars if a tenant had to be let into the building. It was always the moment between ringing the doorbell and her appearing around the corner that paralyzed him. He knew that she must hate him. He was sure she complained to her friends about the stupid kid who moved in upstairs. The stupid farm kid who locked himself out four times in three weeks and does not belong in the city.

When he came out of it, he was angry at himself. He had to try harder not to think about it. He reminded himself that it was throwing all of his belongings into his car and moving to the city was an accomplishment. He had adapted to working in the main branch of the bank, almost without problems. It did not matter that he did not know anyone here. He was where he had always wanted to be. He had his own apartment, right above the superintendent, who by now was sound asleep.

He knew he should have just gone home right after work. At least then he wouldn't have to wake her up; but he couldn't do it. When people started leaving the office to go home, his mind kept going back to the night before. Midnight, and she was standing outside his door, still in the lavender robe. She was screaming. He was sorry, he said. He hadn't realized she could hear him. She just screamed.

When he got hungry, he went alone to a restaurant and pretended to read a newspaper while he ate. At the movies, he tried to act as though he was waiting for someone, looking at his watch every minute and sighing when the previews began. After the movies, he went to the bar alone. He sat at a table in the corner, listened to other people talking and only once thought about how pathetic it was to be afraid. He was also alone, or nearly so, on the platform, and by now it was very late.

From the elevated platform, he could see far down the street, wet and reflective of the ambers, reds and yellows of a city at night. The wind blew gently but steadily, blowing through the spaces between his skin and his clothes, taking heat and anxiety with it.

It was quiet enough that he heard the train coming before he could see it. He watched almost like an animal, as the light spilled down the tracks followed by the train itself, slithering.

This train car was empty as well. He took a seat in the middle, set down his bag, and leaned his elbow against the cold glass. He watched the city move past the window in a sleepy fog of taillights, traffic lights, neon lights.

At the next stop, he watched with his peripheral vision as a old woman stepped into the car and chose a seat across the aisle. She was a black woman, grandmotherly and tired. She sat in a seat that faced the back of the train; riding backwards made him queasy. He wondered where she was coming from so late at night and where she was going. Every possibility he could think of seemed wrong. She was impossible to know.

He looked out of the window again, now pressing his forehead against the glass. As the train began to move again, his face slid down the window, and he did nothing to stop it until his chin touched the rubber seal at the bottom. That is when he noticed the paper square on the seat next to him. He recognized it even before his eyes had focused. It was the prize from a box of Crackerjacks.

He rubbed the small package between his fingers, held it up to the fluorescent lights, and wondered what kind of person would buy Crackerjacks and not care about the surprise. He tore open the paper and smiled when he saw that it was the temporary tattoo. Using his free hand to unbutton the stiff white cuff of his shirt, he rolled the blue-striped sleeve up to his armpit. He peeled the paper backing off of the tattoo and licked his left biceps impishly before pressing the thin paper onto the moist skin. He counted out thirty seconds in his head and then lifted the damp square.

He smiled at the reflection in the window as he flexed his arm; he smiled wider when he saw the heart-with-arrow stretch as his muscles changed shape. He stopped smiling when he noticed the woman across the aisle staring at him.

Embarrassed, he unrolled his sleeve and looked down at his feet. He was buttoning his cuff again when he saw something that made his eyebrows squeeze together. There, under the seat in front of him, were his missing keys.

It is hard to interpret just what this meant. For some people, ending up in the exact seat of the exact car on the exact train would be proof of the existence of God. Most others would at least experience some awe at having the law of probability demonstrated so eloquently in their favors. But this young man was not thinking about the universe. It was almost as if he had expected it. When the keys were lost, he had still been almost certain, unless they had been melted or broken or disintegrated, that the key chain had to be somewhere. That knowledge that the keys still existed turned into a small bit of hope and had always found hope to be worthwhile. Any feelings about the matter however, were overshadowed by something less complicated: he was relieved to avoid the superintendent. He returned the keys to the front pocket of his pants before turning sideways in his seat.

"I just found my keys," he said. The woman, who had been close to sleep, turned her eyes but said nothing. "I lost them this morning. They must have fallen out of my pocket. All day I worry about how I'm going to get back into my apartment, and then I look down and there they are. I must be on the same train that I took this morning. Only it can't be the same train; the seats were different. But they were right there, on the floor." When he stopped speaking, the woman looked down at her hands, paused, and then looked back up at the man.

"It's hard to believe," she said.

"Yes," he replied. "It is hard to believe, isn't it?" They were interrupted by the recorded voice announcing the next stop. He stood and kept his balance by holding onto the bar above the seat. "You be careful out there," he said, and she nodded. He walked along the decelerating train car, the bars steadying him until he made it to the doors. When the train stopped, the doors opened and the wind spilled inside.

"Doors closing," said the voice. The man patted his front pocket, heard the faint sound of metal rubbing against metal, and then stepped off of the train.