Lisa makes sure that her cell phone plan has plenty of anytime minutes because, she told me, most of the time she is unhappy with the people of the present.

Last Tuesday she thought it would be a good idea to call her grandmother's Great Aunt Ida, who lived on a farm in 1863. Lisa had first heard about Aunt Ida in bedtime stories and she showed such fascination with the ancestor that she was presented with Ida’s diary on the eve of her sixteenth birthday. Aunt Ida had been the first woman elected to city council in the state of Wyoming. Even though women could not vote in 1863, there was no law prohibiting them from running for office, and also no law prohibiting women from refusing to sleep with their husbands if they did not vote for Mrs. Ida Mae Hopkins. Unfortunately the telephone was not invented until 1873 and poor Aunt Ida had to spend a week in bed because of the horrible ringing in her ears. Lisa stopped calling when she read about this in the diary.

Over the weekend she called her great grand daughter's best friend. Her name will be Lupita and, in the year 2102, she will be 12 years old. Lisa, not wanting Lupita to know she was from the past, pretended to be doing a survey about drug use in twenty-second century adolescents. It sounded like Lisa's great granddaughter will already be smoking a half a pack a day by the time she is thirteen. This worried Lisa for most of the afternoon but at dinner she decided that if cigarettes are still around one hundred years in the future then they must have found a cure for cancer.

Last night Lisa called the Lisa she had been when she was in high school. The phone contract had strict warnings against calling one's past, but Lisa knew that the sixteen-year-old Lisa, who aspired to be a state representative, would never recognize the soap-opera-addicted, furniture-polishing, wife of a youth-pastor-who-did-not-believe-in-birth-control and consequently mother of six, she would become. Old Lisa did not talk to young Lisa very long. Not wanting to risk changing history she tried the drug survey act again, and was surprised to discover that she had been a terrible liar.

This morning, Lisa called me. I am actually a caveman named Pelto. A few years before I wrote this, I found a rock that was making a ringing noise. A noise I would later learn was a ringtone of "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" from the musical Showboat. I picked up the rock and when I put it up to my ears I heard someone speaking a language that I would also later learn was English. I know that may be hard to believe, but I have a lot of spare time as my wife does most of the hunting. Anyways, I first started talking to Lisa a few weeks back. She called me by accident, (This happens a lot--my phone number is 3.) but we hit it off. She calls me now almost every day, tells me about her life, and keeps me up to date on all of my favorite soap operas. Yesterday she told me about a doctor on a talk show who stressed the importance of keeping a journal and I thought I'd try it. This is my first journal entry. Come to think of it, it's probably the first journal entry. I promise to write in it every day.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Monday, March 13, 2006

Pooh Sticks - an attempt at a poem

Pooh Sticks

The equidistant pines are

more conjured than those

of the second growth.

Rows for running down

and proof of endlessness

while tennis shoes, red that year

or black, not quite touching

the needle sponge.

And the hill. What grass

would be if we let it

and always wet. Tumbles taken

here and here and back

in the woods. Abrasions

often showing under the hems

or as bridges over tan lines

will be gone by September

Then where the horse bridge was

but isn't now but still where

where a girl, haircut crooked,

crooked teeth, father

with a forest beard and the son

who will not describe himself

dropped sticks into the river

and watched them come out on the other side.

Sunday, March 05, 2006

Thrive - Part 10

INT. CAFETERIA - DAY

Bill sits at a table by himself. He has a newspaper and a plate with scrambled eggs, toast and a slice of cantaloupe.

The headline of the newspaper says: "Hospital Director Resigns."

Bill looks down to his plate and picks up the cantaloupe. He takes a bite.

The headline of the newspaper now reads: "CDC: "Aluminum not responsible for memory loss."

Bill is holding a honeydew, there is a bite taken out of it. He takes another.

The headline of the newspaper says: "Bill Janus indicted in hospital scandal."

Bill puts down the paper and uses a knife and fork to cut his steak. Someone coughs behind him. He turns his head and June is standing at the kitchen sink washing dishes. She wipes the back of her hand on a dish towel.

Bill picks up the copy of Gray's Anatomy he has been reading. He looks at a picture of the liver.

Bill cuts the liver and onions on his plate. The sound of people clicking knives on water glasses makes him look over.

Janice sits next to him, she is wearing a wedding dress, he is wearing a tuxedo, he leans over and kisses her. He closes his eyes. When he opens them, he is kissing June, she is wearing a negligee.

Bill is in bed with June, he is wearing purple satin pajama bottoms. June is asleep. Bill gets out of bed and sits down on the floor Indian-style.

Bill plays with legos wearing purple flannel pajamas on the floor of the hospital room. A very old man sits on the bed watching him.

OLD MAN: Do you love me Solomon?

BILL: Is that my name?

Bill looks at the old man for a response. The old man looks confused, he is trying to find words to say.

OLD MAN: Well...um...ummm.

The left side of the screen starts to turn blue in an irregular moving patch. The patch consumes the old man and becomes a vaguely human shaped patch of blue.

BILL: Is that my name?

PATCH OF BLUE: Do you love me Bill?

BILL: Do you love me Solomon?

The patch of blue is now green.

PATCH OF GREEN: Kilimanjaro

Bill sits next to Solomon, everything else is white.

BILL AND SOLOMON: (simultaneously) It's hyphenated.

The patch is now a circle, the color shifts from blue to green and changes in diameter.

CIRCLE: Willy-um-Janus. Solly-mun-Janus

Solomon's face is very big. His lips don't move, his eyes blink rapidly.

SOLOMON: Butler-Janus. It's hyphenated.

CIRCLE: Solly-um-but-ler-willy-mun.

Bill and Solomon's heads are fused together at the back, Bill's face on the right, Solomon's on the left.

BILL AND SOLOMON: Janus.

Absolute Chaos. Several bits of the film overlapping each other, in increasing states of digital decay. Sounds from before, sometimes lines said by the wrong people, nothing disctinctly audible though. Everything progresses toward absolute white which is achieved about thirty seconds before absolute silence.

Credits come out of the white in a neutral gray and scroll to both sides of the frame from the center.

THE END

Friday, March 03, 2006

Thrive - Part 9

Thursday, March 02, 2006

Thrive - Part 8

INT. JANICE AND BILL'S BEDROOM - DAY

Janice and Bill come into the bedroom, it's nine o'clock in the morning and they have just returned from staying up all night in the hospital. Janice goes to the closet and starts to undress. Bill stands in the doorway and looks at her.

JANUS: I can't do this anymore.

JANICE: I know how you feel. It seems impossible that this is happening.

JANUS: No, you don't. You don't know how I feel. This isn't an expression of frustration. I seriously cannot do this any more.

JANICE: What choice do we have?

JANUS: There are some people who are able to do things like this, there are people who can suffer through tragedy and feel like it makes them stronger. I'm not one of them.

JANICE: How do you know? How have you suffered before this?

JANUS: You, I think, are one of those people. You can be the hero in this, the patient one, the longsuffering one. I'm the villain here, I know it. I am designed to be the asshole.

JANICE: You need to go to sleep Bill, we have to go back in four hours.

JANUS: I am the weak one, the one to hate. The one that had to be lost. You can be the one who was somehow able to make it. The woman who's only son is in the hospital, who's husband left her, just when she needed him--

JANICE: What?

JANUS: Who's husband left when things started to look bad, he just dropped her, left everything there his son, his house, and found another life, another woman to live with.

JANICE: Stop it. Bill. Stop it.

JANUS: Who never saw him again.

Janice picks up a shoe from the ground and throws it at him.

JANICE: Quit it right now. How can you say those things?

JANUS: Who fought against him, begged him to stay but he wouldn't listen. When she held onto his feet when she punched him as hard as she could-- which is not very hard, she's a small woman--he pushed her away, he ran, he literally ran out the door, slammed the car door as she stood on the steps crying until she collapsed.

JANICE: Why are you doing this to me now. Stop. Please stop, I can't take this.

JANUS: You can. It's me who can't take it-- and he backed out of the driveway looking her in the eyes the whole time. You see he never had a soul, never really loved her, or his son, and he had to get out.

JANICE: Get out!

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Thrive - Part 7

INT - JANICE'S KITCHEN - DAY

Bill and Janice are preparing food for Solomon's birthday party. Solomon, now fourteen years old is in the dining room, he has a basket of crayons in front of him. He is coloring pages in a coloring book. He draws overlapping squares of color, disregarding the lines on the pages..

Bill cuts beef and chicken into chunks for shish-kabobs, Janice is cutting the vegetables.

JANUS: It was two days late, they don't even charge a late fee for five.

JANICE: You think it's late fees I'm worried about? Bill, that was two days thinking that you had abandoned us, or that you had died, or worse.

JANUS: What's worse than that?

JANICE: There are things worse then death.

JANUS" Yeah, I've heard that before, but nobody can ever tell me what they are. I don't think there's anything worse than that. No matter how much you've accomplished…

JANICE: Don't try to change the subject.

JANUS: No, Janice, this is the problem, no matter how much you've planned and prepared, when you go, there will be something you never did, some part of being alive that you have never experienced. While you're alive there's at least the possibility that some day you'll do it, but when you're dead, you're nothing but a list of what you didn't do.

JANICE: (sarcastic) You know what, you're right, every time I think of Martin Luther King I think of all the things he didn't do.

JANUS: He doesn't think at all any more, he doesn't exist; everything we know about him is made up--what someone else thought about him. Even stuff he wrote down, we only know what it means based on what we think ourselves.

Bill and Janice are preparing food for Solomon's birthday party. Solomon, now fourteen years old is in the dining room, he has a basket of crayons in front of him. He is coloring pages in a coloring book. He draws overlapping squares of color, disregarding the lines on the pages..

Bill cuts beef and chicken into chunks for shish-kabobs, Janice is cutting the vegetables.

JANUS: It was two days late, they don't even charge a late fee for five.

JANICE: You think it's late fees I'm worried about? Bill, that was two days thinking that you had abandoned us, or that you had died, or worse.

JANUS: What's worse than that?

JANICE: There are things worse then death.

JANUS" Yeah, I've heard that before, but nobody can ever tell me what they are. I don't think there's anything worse than that. No matter how much you've accomplished…

JANICE: Don't try to change the subject.

JANUS: No, Janice, this is the problem, no matter how much you've planned and prepared, when you go, there will be something you never did, some part of being alive that you have never experienced. While you're alive there's at least the possibility that some day you'll do it, but when you're dead, you're nothing but a list of what you didn't do.

JANICE: (sarcastic) You know what, you're right, every time I think of Martin Luther King I think of all the things he didn't do.

JANUS: He doesn't think at all any more, he doesn't exist; everything we know about him is made up--what someone else thought about him. Even stuff he wrote down, we only know what it means based on what we think ourselves.

Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Thrive - Part 6

EXT. JANICE'S BACK DOOR - DAY

Bill tries to open the back door to Janice's house but it's locked. He picks up the doormat. Just dirt under there. He looks in the potted plants--nothing. He reaches up over the top of the door, there's the spare key.

He unlocks the door and puts the spare key back.

INT. JANICE'S HOUSE - DAY

Bill walks quietly and carefully through the kitchen into the living room.

The phone rings, startling him.

He walks straight back to a coffee table, opens the drawer. The drawer is full of junk, which he pushes aside, retrieves a photo album, messes the junk up and closes the drawer.

Bill locks the door from the inside before leaving.

EXT. JANICE'S NEIGHBORHOOD - DAY

Bill walks through the back yard, cuts through the neighbor's yards and walks around the corner to where his car is parked.

INT/EXT. BILL'S CAR - DAY

Bill sits in the driver's seat, the photo album is on the seat next to him. He looks at it sitting there. He looks back in the direction of Janice's house. He picks the photo album up.

EXT. JANICE'S NEIGHBORHOOD - DAY

Bill goes back through the neighbor's backyard, this time a little girl is playing in the sand box. He ignores her and goes through to Janice's yard. The little girl runs into her house.

EXT. JANICE'S BACK YARD - DAY

Bill reaches up and gets the spare key to the back door again.

INT/EXT. JANICE'S CAR - DAY

Janice is driving, talking on her cell phone with a hands-free device.

JANICE: I'll be there soon, call me at home.

INT. JANICE'S HOUSE - DAY

Bill walks through the kitchen quickly and into the living room. He opens the drawer. He hears a car pull into the driveway.

JANUS: Fuck.

He puts the photo album back into the drawer, closes it.

He runs back through the kitchen to the back door.

He opens the back door. Janice is standing with a bag of groceries looking through her keys.

JANICE: Bill.

Monday, February 27, 2006

Thrive - Part 5

INT. BILL AND JANICE'S KITCHEN - DAY

Bill winces in expectation

Janice squeezes his fingertip, a drop of blood bulges and starts to run. Janice catches the blood on a blood sugar test strip.

They wait in silence. The blood sugar test machine beeps. Janice looks down.

JANICE: (pleading) Bill.

JANUS: I’m sorry.

JANICE: Drink some water and walk around the block.

JANUS: I know.

JANICE: You’re like a little kid sometimes.

INT. SOLOMON'S BEDROOM - NIGHT

Solomon lies on his back on the top bunk of a sturdy white bunk bed. He stares at the ceiling. His breathing is heavy. He rocks his knee back and forth nervously with increasing speed. Soon he is breathing faster and faster to the point of hyperventilating. Janice approaches the bed.

SOLOMON: I think I'm going crazy.

JANICE: Go take a hot bath.

INT. BATHROOM - NIGHT

Bill sits in a bathtub. Condensation drips from the mirror. June paces back and forth outside the door with a cordless phone to her ear.

JUNE: I don’t know...an hour ago?

Junes disappears. Bill gets out of the tub, dripping. He dries himself off.

JUNE: At his age?

Bill closes the bathroom door, and turns the lock.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

Thrive - Part 4

INT. BILL AND JUNE'S BEDROOM - NIGHT

Bill is undressing down to his boxers. June is brushing her teeth. She spits.

JUNE: I love you Bill.

JANUS: I know June. I always know you do.

JUNE: Bill. He loves you too. Don’t worry.

JANUS: That’s what everyone says. That’s what Janice said.

JUNE: Janice was there?

JANUS: No. On the phone. Don’t worry.

JUNE: I don’t.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

Thrive - Part 3

INT. SOLOMON'S HOSPITAL ROOM - NIGHT

The chart on the bed reads "BUTLER-JANUS, SOLOMON TOBIAS"

Janus sits on Solomon's hospital bed, a cell phone to his ear. Solomon has emptied the bucket of all of the Legos.

JANUS: Janice Butler please.

During the pause, Solomon removes Legos from a small area of the floor and puts them back into the bucket. He curls up in the empty space.

JANICE: (on phone) Hello?

JANUS: It’s Bill. I’m at the hospital.

JANICE: Where in the hospital?

JANUS: In his room. They let me in.

JANICE: When?

JANUS: A few minutes ago.

JANICE: How is he?

JANUS: He hasn’t responded to me yet.

JANICE: You have to ask him direct question.

JANUS: I...I know that. I just wanted to watch him first.

JANICE: You should talk to him. He loves you.

JANUS: I just wanted to call you first.

JANICE: Don’t worry Bill, he won’t break.

JANUS: I wanted to let you know I was here, in case...so you would understand if he mentioned me or something.

JANICE: They would have told me. They keep a record.

JANUS: You’re right. I’m sorry. Sorry to bother you.

JANICE: No, it’s Ok. I understand. Don’t worry about him, just talk to him.

JANUS: I...I will. Thanks.

He hangs over and looks at the boy who is still curled up, his eyes are very wide open.

JANUS: Solomon?

No response.

JANUS: What are you making Solomon?

SOLOMON: The blocks fit together.

JANUS: That looks like a dog...Is that a dog?

SOLOMON: No. It’s blocks.

JANUS: Do you love me Solomon?

Friday, February 24, 2006

Thrive - Part 2

INT. KITCHEN - DAY

Bill Janus sits at his mother's kitchen table with his mother.

MOTHER: Why ‘Solomon?’

JANUS: After Janice’s Uncle.

MOTHER: Why’s he so great?

JANUS: He died as a baby.

MOTHER: You’ve named your first child after a failure to thrive.

JANUS: A second chance to thrive.

MOTHER: Solomon Janus...Solomonjanus...Kilimanjaro.

JANUS: Simon Butler-Janus.

MOTHER: Mother’s maiden name as a middle name. Just like you.

JANUS: Butler-Janus. It’s hyphenated. His middle name is Tobias.

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Thrive - Part 1

INT. WAITING ROOM - NIGHT

BILL JANUS sits on a waiting room bench in a hospital. He stares into the camera, his eyes questioning the audience from the very beginning. Why are they watching him at a time like this? Why is there a time like this? He is staring like he knows that he has been created to suffer for the entertainment of strangers. He pauses in total resignation to whatever evil has caused him to exist, and then is overcome by the idea that he was placed here to suffer so that others may suffer less.

A voice comes from behind him.

NURSE: Mr. Janus.

Janus holds his stare for a second longer, then looks over his shoulder slightly bewildered. A nurse stands over him. There is no one else in the waiting room.

JANUS: Yes?

NURSE: I will take you in.

Janus stands up and takes a step toward her, remembers his bag, steps back and retrieves it. Looks up at the nurse realizing that she is taller than he is.

JANUS: Ok.

The nurse leaves the waiting room through a door and Janus follows. They walk through a long hospital corridor, in the first rooms the oldest people Bill has ever seen are sitting up in beds, they are connected to respirators and intravenous tubes. They are as brittle as dead spiders. Janus and the nurse turn a corner, now rooms contain retirement aged men and women eaten by cancers, drowning from congestive heart failure. They turn again and pass middle aged people, wheezing because their lungs do not work or yellow with kidney failure. The next turn leads to young adults, accident victims, blood-stained sheets. The final turn leads to children: leukemia, birth defects. The nurse stops in front of a doorway.

NURSE: In here.

Janus nods at her and enters. His seven-year-old son, SOLOMON, sits on the rough grey carpeting. He is taking legos out of a bucket. He sticks two or three together and sets them onto the floor, then gets a few more, sticks them together and puts them somewhere else. He is already surrounded by a patternless mess of different-sized Lego clusters.

JANUS: Solomon.

The boy looks up at his father.

Monday, February 20, 2006

Four Hours in Glasgow - Part 6

It was raining again when I left the Cathedral. I went around to the back to see the cemetery. It was even foggier in back. I walked along a stone path. I looked up. The cemetery was on a hill. The gravestones slanted towards me, covered in soot and soil. I looked down and saw that it was not a stone path but that I was standing on grave markers embedded in the ground. I jumped back and in my peripheral vision I saw a figure, a dark man, a bum, sleeping in one of the crypts. He looked at me.

I left the Cathedral and headed for the train station again. The further I walked, the more unbearable my backpack became. I reached around and fastened the waist-straps at my bellybutton.

I wonder if the support straps on backpacks make them at all easier to carry or if the feeling of being hugged just makes the ordeal more bearable. Either way I made it to the train station and the train to London was waiting with two cars of unreserved seats. I sat down and I listened.

I tried to console myself by blaming my failure on Glasgow—on the weight of my backpack—on the rain. I told myself that I like riding on the train more than being in a place and that I would be better to enjoy the train ride home than to try and spend the night in a city I didn’t like. I wonder if I was right.

In front of me a roughish looking Scottish couple with red hair and leather jackets was speaking caring words to and old lady. They arranged sandwiches and juice boxes on the table in front of here and kept telling her not to worry. The announcement came for “those not intending to travel to leave the train” and the couple stood outside the car and waved and smoked.

And then the train started. Out the window there was grey and grass and sheep and heather. A Scottish conductor checked my Britrail Pass and moved to the young lady across the aisle from me. She appeared to be around seventeen years old and was sitting with a one-year-old baby with silver stud earrings and seven or eight bracelets. The girl tried to pass off a ticket that had already been punched and the conductor spoke to her so sweetly and understandingly yet he still made her pay. As the trip progressed the baby, whom I soon learned was named Nicole, began to wander the train, further and further from her mother. Wherever she crawled it seemed that children would appear wanting to play with her. Among them was a seven-year-old with round glasses and a thick brogue who was increasingly worried that Nicole would ruin his Pokemon game. Nicole’s mother tried desperately to keep her daughter to sit still. She even resorted to having her was the train’s windows with baby wipes. As I watched this young woman from between the headrests she looked to me like a mix of tough and beautiful, caring and suspicious. I felt sorry for her and proud of her. I was fascinated.

Eventually, the clouds dispersed again and the land began to glow in the magic hour. Nicole and her mother disembarked and I watched the sunset and the moon rise from among the sheep to take its place.

A new conversation gradually took my attention. At first, I could only hear the boy. He was yelling stream of consciousness facts in the thick voice of a Scottish Lad. I peered over my seat and understood. It was the Pokemon boy and he was talking to the old lady, he started addressing her as “Gran”.

“Yesterday,” he said, “Yesterday was the Queen’s birthday and she was a hundred.” Gran Nodded and whispered something into his ear. “You’re not! You are not one hundred years old,” he shouted into her hearing aid. She whispered again. “You’re not sixty-three,” he replied.

“The problem with me,” he said. “The only problem with me is that I can’t always finish my work. There’s this boy Jimmy and he keeps me from finishin’.” His vocal tone rose with each sentence.

Eventually, she said something out loud. “The train’s quiet and I can hear ya’ fine.” By then it was dark and as the Scottish grandmother and a grandson whispered to each other I watched the stars speed by listening to the rhythm of the train.

The train at last arrived in London. I got off feeling numb—-not triumphant or defeated. I wedged my way through the crowd and stepped quickly to the end of the platform. I noticed that my shoe was untied and as I kneeled down to tie it I heard a voice.

“Mah!” I heard, then the pat pat pat of a running child. “Mah! Mah!”

In front of me a youngish, motherly looking woman held her hands out.

“Mah!” I heard it one more time before I saw him. The Pokemon boy ran past me and jumped into the arms of his waiting mother. She swung him around and I understood why I had gone to Glasgow.

I left the Cathedral and headed for the train station again. The further I walked, the more unbearable my backpack became. I reached around and fastened the waist-straps at my bellybutton.

I wonder if the support straps on backpacks make them at all easier to carry or if the feeling of being hugged just makes the ordeal more bearable. Either way I made it to the train station and the train to London was waiting with two cars of unreserved seats. I sat down and I listened.

I tried to console myself by blaming my failure on Glasgow—on the weight of my backpack—on the rain. I told myself that I like riding on the train more than being in a place and that I would be better to enjoy the train ride home than to try and spend the night in a city I didn’t like. I wonder if I was right.

In front of me a roughish looking Scottish couple with red hair and leather jackets was speaking caring words to and old lady. They arranged sandwiches and juice boxes on the table in front of here and kept telling her not to worry. The announcement came for “those not intending to travel to leave the train” and the couple stood outside the car and waved and smoked.

And then the train started. Out the window there was grey and grass and sheep and heather. A Scottish conductor checked my Britrail Pass and moved to the young lady across the aisle from me. She appeared to be around seventeen years old and was sitting with a one-year-old baby with silver stud earrings and seven or eight bracelets. The girl tried to pass off a ticket that had already been punched and the conductor spoke to her so sweetly and understandingly yet he still made her pay. As the trip progressed the baby, whom I soon learned was named Nicole, began to wander the train, further and further from her mother. Wherever she crawled it seemed that children would appear wanting to play with her. Among them was a seven-year-old with round glasses and a thick brogue who was increasingly worried that Nicole would ruin his Pokemon game. Nicole’s mother tried desperately to keep her daughter to sit still. She even resorted to having her was the train’s windows with baby wipes. As I watched this young woman from between the headrests she looked to me like a mix of tough and beautiful, caring and suspicious. I felt sorry for her and proud of her. I was fascinated.

Eventually, the clouds dispersed again and the land began to glow in the magic hour. Nicole and her mother disembarked and I watched the sunset and the moon rise from among the sheep to take its place.

A new conversation gradually took my attention. At first, I could only hear the boy. He was yelling stream of consciousness facts in the thick voice of a Scottish Lad. I peered over my seat and understood. It was the Pokemon boy and he was talking to the old lady, he started addressing her as “Gran”.

“Yesterday,” he said, “Yesterday was the Queen’s birthday and she was a hundred.” Gran Nodded and whispered something into his ear. “You’re not! You are not one hundred years old,” he shouted into her hearing aid. She whispered again. “You’re not sixty-three,” he replied.

“The problem with me,” he said. “The only problem with me is that I can’t always finish my work. There’s this boy Jimmy and he keeps me from finishin’.” His vocal tone rose with each sentence.

Eventually, she said something out loud. “The train’s quiet and I can hear ya’ fine.” By then it was dark and as the Scottish grandmother and a grandson whispered to each other I watched the stars speed by listening to the rhythm of the train.

The train at last arrived in London. I got off feeling numb—-not triumphant or defeated. I wedged my way through the crowd and stepped quickly to the end of the platform. I noticed that my shoe was untied and as I kneeled down to tie it I heard a voice.

“Mah!” I heard, then the pat pat pat of a running child. “Mah! Mah!”

In front of me a youngish, motherly looking woman held her hands out.

“Mah!” I heard it one more time before I saw him. The Pokemon boy ran past me and jumped into the arms of his waiting mother. She swung him around and I understood why I had gone to Glasgow.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

St. Anthony and the Key Chain - Part 5

He had never been the only person in a train car before. He noticed that the ride was bumpier when the train was not packed with a rush hour crowd. The rhythmic rocking of the train made it easy for him to think about nothing. Thinking about nothing was not worrying. He was not worrying if moving to the city by himself had been a mistake. He was not worrying about getting mugged on the walk between the train stop and his apartment. Most importantly, he was not worrying about what would happen when he got back to his apartment at two o'clock in the morning with no keys.

Only when the train had reached the end of its line, far beyond his stop, did he become aware again. Stoic, he crossed the platform, and, even though he knew it would be at least twenty minutes, he waited patiently for a train in the opposite direction.

A few minutes of waiting in the silence with nothing to distract him, and he was back to the worrying that had perforated his entire day. It started with the memory of a feeling. He was there again, standing in the chilly foyer, waiting for the superintendent to let him in. That was the most humiliating part of the memory. Worse than the image of her in a dirty lavender bathrobe pressing her lips together in general disapproval of his existence. Worse than remembering that she had made him wait outside her door as she looked for her copy of his lease. Even worse than when she made him read aloud the section that said the superintendent had the right to charge ten dollars if a tenant had to be let into the building. It was always the moment between ringing the doorbell and her appearing around the corner that paralyzed him. He knew that she must hate him. He was sure she complained to her friends about the stupid kid who moved in upstairs. The stupid farm kid who locked himself out four times in three weeks and does not belong in the city.

When he came out of it, he was angry at himself. He had to try harder not to think about it. He reminded himself that it was throwing all of his belongings into his car and moving to the city was an accomplishment. He had adapted to working in the main branch of the bank, almost without problems. It did not matter that he did not know anyone here. He was where he had always wanted to be. He had his own apartment, right above the superintendent, who by now was sound asleep.

He knew he should have just gone home right after work. At least then he wouldn't have to wake her up; but he couldn't do it. When people started leaving the office to go home, his mind kept going back to the night before. Midnight, and she was standing outside his door, still in the lavender robe. She was screaming. He was sorry, he said. He hadn't realized she could hear him. She just screamed.

When he got hungry, he went alone to a restaurant and pretended to read a newspaper while he ate. At the movies, he tried to act as though he was waiting for someone, looking at his watch every minute and sighing when the previews began. After the movies, he went to the bar alone. He sat at a table in the corner, listened to other people talking and only once thought about how pathetic it was to be afraid. He was also alone, or nearly so, on the platform, and by now it was very late.

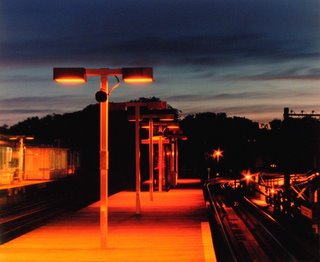

From the elevated platform, he could see far down the street, wet and reflective of the ambers, reds and yellows of a city at night. The wind blew gently but steadily, blowing through the spaces between his skin and his clothes, taking heat and anxiety with it.

It was quiet enough that he heard the train coming before he could see it. He watched almost like an animal, as the light spilled down the tracks followed by the train itself, slithering.

This train car was empty as well. He took a seat in the middle, set down his bag, and leaned his elbow against the cold glass. He watched the city move past the window in a sleepy fog of taillights, traffic lights, neon lights.

At the next stop, he watched with his peripheral vision as a old woman stepped into the car and chose a seat across the aisle. She was a black woman, grandmotherly and tired. She sat in a seat that faced the back of the train; riding backwards made him queasy. He wondered where she was coming from so late at night and where she was going. Every possibility he could think of seemed wrong. She was impossible to know.

He looked out of the window again, now pressing his forehead against the glass. As the train began to move again, his face slid down the window, and he did nothing to stop it until his chin touched the rubber seal at the bottom. That is when he noticed the paper square on the seat next to him. He recognized it even before his eyes had focused. It was the prize from a box of Crackerjacks.

He rubbed the small package between his fingers, held it up to the fluorescent lights, and wondered what kind of person would buy Crackerjacks and not care about the surprise. He tore open the paper and smiled when he saw that it was the temporary tattoo. Using his free hand to unbutton the stiff white cuff of his shirt, he rolled the blue-striped sleeve up to his armpit. He peeled the paper backing off of the tattoo and licked his left biceps impishly before pressing the thin paper onto the moist skin. He counted out thirty seconds in his head and then lifted the damp square.

He smiled at the reflection in the window as he flexed his arm; he smiled wider when he saw the heart-with-arrow stretch as his muscles changed shape. He stopped smiling when he noticed the woman across the aisle staring at him.

Embarrassed, he unrolled his sleeve and looked down at his feet. He was buttoning his cuff again when he saw something that made his eyebrows squeeze together. There, under the seat in front of him, were his missing keys.

It is hard to interpret just what this meant. For some people, ending up in the exact seat of the exact car on the exact train would be proof of the existence of God. Most others would at least experience some awe at having the law of probability demonstrated so eloquently in their favors. But this young man was not thinking about the universe. It was almost as if he had expected it. When the keys were lost, he had still been almost certain, unless they had been melted or broken or disintegrated, that the key chain had to be somewhere. That knowledge that the keys still existed turned into a small bit of hope and had always found hope to be worthwhile. Any feelings about the matter however, were overshadowed by something less complicated: he was relieved to avoid the superintendent. He returned the keys to the front pocket of his pants before turning sideways in his seat.

"I just found my keys," he said. The woman, who had been close to sleep, turned her eyes but said nothing. "I lost them this morning. They must have fallen out of my pocket. All day I worry about how I'm going to get back into my apartment, and then I look down and there they are. I must be on the same train that I took this morning. Only it can't be the same train; the seats were different. But they were right there, on the floor." When he stopped speaking, the woman looked down at her hands, paused, and then looked back up at the man.

"It's hard to believe," she said.

"Yes," he replied. "It is hard to believe, isn't it?" They were interrupted by the recorded voice announcing the next stop. He stood and kept his balance by holding onto the bar above the seat. "You be careful out there," he said, and she nodded. He walked along the decelerating train car, the bars steadying him until he made it to the doors. When the train stopped, the doors opened and the wind spilled inside.

"Doors closing," said the voice. The man patted his front pocket, heard the faint sound of metal rubbing against metal, and then stepped off of the train.

Friday, February 03, 2006

Four Hours in Glasgow - Part 5

It only took a block or so of walking before my shoulders began to hurt but I bucked up and forced myself the ten blocks or so to the Cathedral. I watched so many strange combinations of those looking very old and those looking very young standing at the street corners. Traffic lights seemed to last longer and everything was telling me that I was simply not tough enough for Glasgow.

Glasgow Cathedral

Then the Cathedral poked over the Horizon. It surprised me because I thought it was going to be the much larger building across the street but once I saw it, it was unmistakable.

The whole structure was blackened like it had been barbequed, and roofed with a soft fuzzy-green copper. Dark stained glass and a sign saying “Cathedral Visitors to the Right.”

There was a peaceful trickle of Germans Japanese and others like me (white, disheveled, large backpack and not talking to preserve the mystery of their origin.) The inside was amazing. The echo of the door handle’s crash, as I entered, bounced around the gothic ceiling. There were two separate post card racks, one of Glasgow and one of the Cathedral and two separate Auntie Jean types at desks beside them. I tried to look at the stained glass but the organ music, strange chromatic baroque-ness, coming from the chapel pulled me in.

At first glance I thought that a church service was going on. The back and front rows of the pews were filled with people who were looking at the ground. Suddenly one got up and snapped a picture, revealing that we were all tourists.

I sat in a pew and peeled the bag from my shoulders. I stared at the ceiling and prayed—for myself, for my family, for The Campout but I forgot to finish.

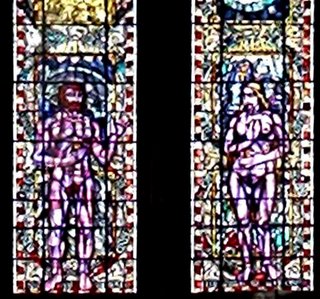

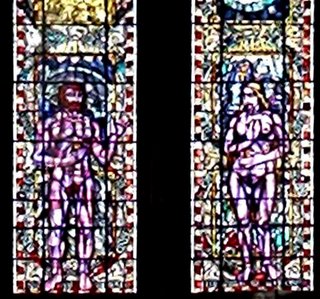

The music ended and I completed my tour. It was wonderful but not in a particularly describable way. There was repetitiveness: every corner was the chapel of saint someone-or-other, every stained glass window a restoration by some Glasgow Guild. But it was also varied. The Nurses Chapel had flags, some had plaques, some relics. Some windows had abstract patterns. Some had pictures.

The largest window was a giant purple depiction of Adam and Eve. Detailed right down to orange pubic hair. Not ideals but humans--sinners.

Original of the Species

I bought two postcards after waiting behind a guy who didn’t speak English. The old lady at the counter was kind and smiley and patient. I shifted my backpack.

Glasgow Cathedral

Then the Cathedral poked over the Horizon. It surprised me because I thought it was going to be the much larger building across the street but once I saw it, it was unmistakable.

The whole structure was blackened like it had been barbequed, and roofed with a soft fuzzy-green copper. Dark stained glass and a sign saying “Cathedral Visitors to the Right.”

There was a peaceful trickle of Germans Japanese and others like me (white, disheveled, large backpack and not talking to preserve the mystery of their origin.) The inside was amazing. The echo of the door handle’s crash, as I entered, bounced around the gothic ceiling. There were two separate post card racks, one of Glasgow and one of the Cathedral and two separate Auntie Jean types at desks beside them. I tried to look at the stained glass but the organ music, strange chromatic baroque-ness, coming from the chapel pulled me in.

At first glance I thought that a church service was going on. The back and front rows of the pews were filled with people who were looking at the ground. Suddenly one got up and snapped a picture, revealing that we were all tourists.

I sat in a pew and peeled the bag from my shoulders. I stared at the ceiling and prayed—for myself, for my family, for The Campout but I forgot to finish.

The music ended and I completed my tour. It was wonderful but not in a particularly describable way. There was repetitiveness: every corner was the chapel of saint someone-or-other, every stained glass window a restoration by some Glasgow Guild. But it was also varied. The Nurses Chapel had flags, some had plaques, some relics. Some windows had abstract patterns. Some had pictures.

The largest window was a giant purple depiction of Adam and Eve. Detailed right down to orange pubic hair. Not ideals but humans--sinners.

Original of the Species

I bought two postcards after waiting behind a guy who didn’t speak English. The old lady at the counter was kind and smiley and patient. I shifted my backpack.

Monday, January 30, 2006

Four Hours in Glasgow - Part 4

Down the block there was a sign for a three-course lunch—-"only four Pounds ninety-five"-—and a picture of a fish pointing up the stairs. “Best Fish Tea in Britain” it said. It took me a moment to clear the idea of a tea bag full of guppies and I started climbing. I waited at the landing while old lady to stumbled down the long staircase and then for an old man to stumble up them. These did not seem like good omens but I entered anyway, possessed by the strange “who cares” courage that can take me without warning. Actually I think the main source of the courage was a desire to relieve myself of the weight on my back. Despite Glasgow being a big, bustling city I couldn’t find anywhere on the streets to sit down. There was nowhere to stop and pull out the “Let’s Go” which was much bulkier and more embarrassing than the London A-Z which, I discovered, was carried by pretty much everyone and not just tourists.

Either way I entered “The Tree’s Family Restaurant” and sat in the no-smoking section because the table was smaller.

A young, sort of tough looking, blonde waitress was at my table almost immediately. She asked what I wanted to order in a startling thick brogue. I wondered if there was a physical border you could cross and hear one dialect on one side and one on the other.

I asked how the three-course lunch worked and, like most people who have been asked a question by me, she answered by saying “What?”

I asked again, paying more attention to my lips and teeth. I ordered the soup (scotch broth of course) and fish and chips. While I waited for the soup I slipped the “Let’s Go” out of the bag and quickly memorized the path to Glasgow Cathedral. The soup came. Having not eaten since the night before, the soup felt like life in my stomach. It was warm and thick and salty and I scraped the bowl of its last bits. I thought about, but decided against, holding my fork in the right hand.

I felt very American and I was sure everyone in the restaurant (all fifteen senior citizens) would notice if I did it wrong. I think I cleaned that plate cleaner that I have ever left a plate before, and it was time to choose dessert. I asked for the trifle and she said, “Aye.” My heart leapt. I had left London after all.

When the trifle was gone I suffered a small panic attack about the acceptability of my English money. I knew that English and Scottish bills are interchangeable but there was still that fear. The bill came on a plate and I covered it with a ten-pound note. Just as I was about to worry about whether I was supposed to carry it to the cash register, a waiter snatched it up and replaced it with a Scottish fiver. I put the purple bank note into the secret compartment of my wallet with my leftover American money, re-strapped my backpack and bounced down the stairs.

I was temporarily elated as I started towards the cathedral. It had been a long time since I had eaten such a complete meal and the feeling of peas in my stomach warmed against the rain.

Either way I entered “The Tree’s Family Restaurant” and sat in the no-smoking section because the table was smaller.

A young, sort of tough looking, blonde waitress was at my table almost immediately. She asked what I wanted to order in a startling thick brogue. I wondered if there was a physical border you could cross and hear one dialect on one side and one on the other.

I asked how the three-course lunch worked and, like most people who have been asked a question by me, she answered by saying “What?”

I asked again, paying more attention to my lips and teeth. I ordered the soup (scotch broth of course) and fish and chips. While I waited for the soup I slipped the “Let’s Go” out of the bag and quickly memorized the path to Glasgow Cathedral. The soup came. Having not eaten since the night before, the soup felt like life in my stomach. It was warm and thick and salty and I scraped the bowl of its last bits. I thought about, but decided against, holding my fork in the right hand.

I felt very American and I was sure everyone in the restaurant (all fifteen senior citizens) would notice if I did it wrong. I think I cleaned that plate cleaner that I have ever left a plate before, and it was time to choose dessert. I asked for the trifle and she said, “Aye.” My heart leapt. I had left London after all.

When the trifle was gone I suffered a small panic attack about the acceptability of my English money. I knew that English and Scottish bills are interchangeable but there was still that fear. The bill came on a plate and I covered it with a ten-pound note. Just as I was about to worry about whether I was supposed to carry it to the cash register, a waiter snatched it up and replaced it with a Scottish fiver. I put the purple bank note into the secret compartment of my wallet with my leftover American money, re-strapped my backpack and bounced down the stairs.

I was temporarily elated as I started towards the cathedral. It had been a long time since I had eaten such a complete meal and the feeling of peas in my stomach warmed against the rain.

Thursday, January 26, 2006

St. Anthony and the Keys - Part 4

She slid the key chain across the scanner, just like she had done with tens of thousands of groceries, coupons and key chains before. The motion sensor turned on the laser. The laser was absorbed by the thin black lines and reflected by the white plastic between them. The computer translated that pulse into a number that, in turn, it translated into an address in a database. Ten kilobytes of information traveled just less than six miles at three hundred million meters per second and, upon arrival produced the brief high-pitched beep that still satisfied her each time she heard it.

She switched off the light at her station before picking up the phone and dialing the number at the top of the screen. A very tired woman answered. It was the emergency number of a veterinary hospital. The number must have been changed or faked. She checked the name again and realized that it was fake too. Sandy Klaus. The address section said just "North Pole". He or she must have applied for the card around Christmas time.

This fascinated her. Who would be so paranoid as to give a fake name to the grocery store? Had the store been busier she would have thrown away the keys right there, but she was curious and so she went deeper into the customer’s record.

In a few seconds, she was analyzing a list of all the groceries the customer had bought over the last two years. Having been a check-out girl since high school, she thought she could tell a lot about a person by the groceries he or she bought.

She knew it was a man by his brand of shaving cream. Always the same kind too, even when it was not on sale. He was not as loyal to his deodorant, however. He bought whatever was new or improved.

Further in, she noticed that he had recently moved to the city. Up until one month ago, he shopped at a grocery store on the other side of the state; the country, she thought. She began to create a picture of him in her mind.

He was alone in the city, shy probably. He was single; she was sure of it. Half gallons of milk always gave that away. But he could cook. He bought a lot of spices and oils and strange produce like leeks and artichokes. He ate meat but in moderation. He bought steaks and lamb chops, but no pork. He took vitamins.

On Friday nights, he often bought a slab of fancy cheese and a bottle of wine. But he had not done so in the last two months. She imagined him showing up at her door, setting the bottle on the kitchen counter while she set the table with a plate for the cheese and two wine glasses.

She continued to imagine him long after she was finished looking at his record. She gave him a name and a college degree, tropical fish and a newspaper to read in the mornings and before bed. She gave him a face. She made him a little funny looking but with beautiful dark eyes. She stared at him in her mind and thought she felt a bit warmer inside.

She imagined him waking up in the morning in blue and white striped pajamas. As she balanced her drawer, he was shaving off the moustache she had told him she didn’t like. She rang up one last figure, added a crinkled dollar bill to her drawer before locking it, and picked up a box of Crackerjacks for the ride home.

She put the key chain into her purse when she left, pretending he had given her the spare keys to his apartment. She played with the keys on her lap during the ride home. She imagined him getting onto the train and sitting next to her. He would see the keys out of the corner of his eye and ask her how she got them. She would tell him, and, full of surprise and gratitude, he would ask to buy her coffee, and that is where it ended.

Her stop had arrived. Through the window she could see a man standing on the platform. He was looking at a train schedule and she thought he looked troubled or confused. He had a moustache. She approached him as she stepped off of the train.

“Are you lost?”

She switched off the light at her station before picking up the phone and dialing the number at the top of the screen. A very tired woman answered. It was the emergency number of a veterinary hospital. The number must have been changed or faked. She checked the name again and realized that it was fake too. Sandy Klaus. The address section said just "North Pole". He or she must have applied for the card around Christmas time.

This fascinated her. Who would be so paranoid as to give a fake name to the grocery store? Had the store been busier she would have thrown away the keys right there, but she was curious and so she went deeper into the customer’s record.

In a few seconds, she was analyzing a list of all the groceries the customer had bought over the last two years. Having been a check-out girl since high school, she thought she could tell a lot about a person by the groceries he or she bought.

She knew it was a man by his brand of shaving cream. Always the same kind too, even when it was not on sale. He was not as loyal to his deodorant, however. He bought whatever was new or improved.

Further in, she noticed that he had recently moved to the city. Up until one month ago, he shopped at a grocery store on the other side of the state; the country, she thought. She began to create a picture of him in her mind.

He was alone in the city, shy probably. He was single; she was sure of it. Half gallons of milk always gave that away. But he could cook. He bought a lot of spices and oils and strange produce like leeks and artichokes. He ate meat but in moderation. He bought steaks and lamb chops, but no pork. He took vitamins.

On Friday nights, he often bought a slab of fancy cheese and a bottle of wine. But he had not done so in the last two months. She imagined him showing up at her door, setting the bottle on the kitchen counter while she set the table with a plate for the cheese and two wine glasses.

She continued to imagine him long after she was finished looking at his record. She gave him a name and a college degree, tropical fish and a newspaper to read in the mornings and before bed. She gave him a face. She made him a little funny looking but with beautiful dark eyes. She stared at him in her mind and thought she felt a bit warmer inside.

She imagined him waking up in the morning in blue and white striped pajamas. As she balanced her drawer, he was shaving off the moustache she had told him she didn’t like. She rang up one last figure, added a crinkled dollar bill to her drawer before locking it, and picked up a box of Crackerjacks for the ride home.

She put the key chain into her purse when she left, pretending he had given her the spare keys to his apartment. She played with the keys on her lap during the ride home. She imagined him getting onto the train and sitting next to her. He would see the keys out of the corner of his eye and ask her how she got them. She would tell him, and, full of surprise and gratitude, he would ask to buy her coffee, and that is where it ended.

Her stop had arrived. Through the window she could see a man standing on the platform. He was looking at a train schedule and she thought he looked troubled or confused. He had a moustache. She approached him as she stepped off of the train.

“Are you lost?”

Monday, January 23, 2006

School Play - A Short Screenplay

Sir Andrew begs for forgiveness.

INT. THIRD GRADE CLASSROOM - DAY

About fifteen third graders sit in a circle on a large area rug in an enormous experimental class room. The room has three different levels. A pentagonal section in the back of the room is raised above the floor on three step like tiers. It has a piano on it and rolling carts filled with musical instruments. The middle of the room is a pit of sorts sunken three steps below the floor. The rug is here the rest is empty and can be used for games and running around. The ground-level portion of the room has different configurations of work tables some with computers some with art supplies, etc.

CELICE, the teacher, is a twenty three year old woman with shoulder length brown hair. She wears navy blue corduroy overalls over a plain long sleeved raspberry top is also in the circle.

ESTELLA: We could... I don't know.

CELICE: It's ok Estella, speak up, I'm sure it's a good idea.

ESTELLA: Could we do a play?

CELICE: That's an interesting idea. Does anyone else want to do a play?

ESTELLA: Could we do a play?

CELICE: That's an interesting idea. Does anyone else want to do a play?

The class assents.

CELICE: What play should we do?

LUCY: Let's do Cats.

CELICE : I don't think that's possible. In order to do a play you have to get permission. And Cats is currently playing on Broadway and usually they won't give permission if the play is still running. There are lots of plays that we could get permission for, or if we do a play that was written long enough ago, we can do it without permission and it won't cost us any money. For instance we could do a play by William Shakespeare.

LUCY: Or could we write it ourselves.

CELICE: That's a very creative idea Lucy.

What would we want to write a play about?

LUCY: No, I mean we could write our own play of Cats.

CELICE: Does anyone else want to do a play about cats?

LUCY: Not a play about cats, we could write Cats ourselves.

CELICE: I don't think I understand.

LUCY: I'll get some paper and we'll start writing it you'll see what I mean.

CELICE: Um ok.

CELICE: What play should we do?

LUCY: Let's do Cats.

CELICE : I don't think that's possible. In order to do a play you have to get permission. And Cats is currently playing on Broadway and usually they won't give permission if the play is still running. There are lots of plays that we could get permission for, or if we do a play that was written long enough ago, we can do it without permission and it won't cost us any money. For instance we could do a play by William Shakespeare.

LUCY: Or could we write it ourselves.

CELICE: That's a very creative idea Lucy.

What would we want to write a play about?

LUCY: No, I mean we could write our own play of Cats.

CELICE: Does anyone else want to do a play about cats?

LUCY: Not a play about cats, we could write Cats ourselves.

CELICE: I don't think I understand.

LUCY: I'll get some paper and we'll start writing it you'll see what I mean.

CELICE: Um ok.

Lucy runs and gets a pad of paper.

LUCY: Ok let's start the play in a junkyard with lots of cats in it.

What should their names be?

ESTELLA: Gerizzabella.

Lucy writes it down.

DAVID: Rum Tum Tugger

TINA: Mr. Mistopholes

LUCY: and how about Old Deutoronomy

CELICE: Wait, aren't those the names of the cats in Cats.

LUCY: Exactly. We can think of the rest of the names later.

MEGAN: Oh, Jennyanydots.

LUCY: Ok got her, now what should happen? I think it should start with an opening number.

CELICE: Wait wait, are we sure we want to use the same names as the cats in the play?

ESTELLA: We came up with those names ourselves.

CELICE: No you---

SAM: Let's call the opening number, um "Jelly" cats.

LUCY: It's good but maybe something longer than "jelly" a funnier word.

TINA: How about "jellicle?"

LUCY: Good! The first song will be called Jellicle Cats.

MEGAN: We need a show stopper. I'm thinking maybe something called "Memory"

LUCY: Ooh, good idea, I like the way that sounds.I have some ideas for the words already but let's come up with a plot first.

CELICE: No, no, no. I know that there is a song called Memory in the real play Cats.

DAVID: We're writing a real play!

Celice does not know what to do.

INT. CLASSROOM - NIGHT

Rows of chairs are set up around the raised stage area of the classroom and are filled with parents. On the stage the kids are dressed in costumes exactly like the ones in the Broadway production of Cats. Lucy is standing on a giant tire that is lifted up toward the ceiling a fog machine spills clouds of smoke across the classroom. A real theatre orchestra plays the Cats' ending music from.

EXT. FRONT OF SCHOOL - NIGHT

A couple of dads stand outside smoking as excited kids in cat costumes are led out to the parking lot.

A couple of dads stand outside smoking as excited kids in cat costumes are led out to the parking lot.

DAD ONE: (discreetly) So, what did you think?

DAD TWO: Well, not bad for something written by third graders.

DAD TWO: Well, not bad for something written by third graders.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Four Hours in Glasgow - Part 3

It was 12:15pm when I arrived. I was shivering in Glasgow Central Station. I sat down and extracted my jacket from my backpack.

I stepped onto Union Street and into shock. I can’t say exactly what I expected but I can say what I wanted. I wanted a vacation from London. A small, friendly place--somewhere to eat and sleep and wander. What I got, on first glance, was still London. But it was Glasgow as well--much colder and sadder and cockier than London. And it was drizzling.

I stepped into a crowd and tried to direct myself to the tourist’s office by memory. I ended up in the shopping district. Crowds of activists and socialists and shopping bags. Something in me panicked. I felt like everyone could see that I didn’t belong there; that I was some snotty rude American kid and who the hell did I think I was trying to visit their city. Almost automatically I headed back to the station. The next train back to London wasn’t until four.

So I stepped back out. It was spooky. In the drizzle I kept looking into faces for pieces of myself. Logically, I knew there was little chance, but this place, at least in my head, was full of my ancestors.

I stepped onto Union Street and into shock. I can’t say exactly what I expected but I can say what I wanted. I wanted a vacation from London. A small, friendly place--somewhere to eat and sleep and wander. What I got, on first glance, was still London. But it was Glasgow as well--much colder and sadder and cockier than London. And it was drizzling.

I stepped into a crowd and tried to direct myself to the tourist’s office by memory. I ended up in the shopping district. Crowds of activists and socialists and shopping bags. Something in me panicked. I felt like everyone could see that I didn’t belong there; that I was some snotty rude American kid and who the hell did I think I was trying to visit their city. Almost automatically I headed back to the station. The next train back to London wasn’t until four.

So I stepped back out. It was spooky. In the drizzle I kept looking into faces for pieces of myself. Logically, I knew there was little chance, but this place, at least in my head, was full of my ancestors.

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Four Hours in Glasgow - Part 2

The magazine stand opened and I joined the stampede inside to buy a Coke for breakfast and some water just in case. I spent Ben’s Change. While I was in line for the cashier, the arrival my train to Glasgow was announced so I picked up my bag and made for my seat.

I shoved my bag under the seat and drank my breakfast. Suddenly the train was off. I was going to Glasgow.

I was facing the back of the train. I hate that. Things disappear before you can figure out what they are. The ride was a long, absent six hours. People got on and off. I wrote a bit, read even less, and slept not at all.

It had been sunny in London that morning. Well sunny for London, but as we left the clouds ganged up in layers. For hours I stared out the window watching the dull hazy scenery run away from me, reading about each town in the guide book as I passed it.

I had read earlier about the Lake District, how it had been an inspiration to the Romantic poets. I was excited to see it, even though I never really appreciated the Romantic poets. I wondered if I’d be able to tell when we passed it. Then suddenly the flat pastoral scenery broke into hills unlike any I had seen before. They were green and grooved a flowing.

I was mesmerized. Then just as suddenly the Lake District ran away form me the clouds returned and the land changed to scraggy grass and heather. I had crossed into Scotland.

I shoved my bag under the seat and drank my breakfast. Suddenly the train was off. I was going to Glasgow.

I was facing the back of the train. I hate that. Things disappear before you can figure out what they are. The ride was a long, absent six hours. People got on and off. I wrote a bit, read even less, and slept not at all.

It had been sunny in London that morning. Well sunny for London, but as we left the clouds ganged up in layers. For hours I stared out the window watching the dull hazy scenery run away from me, reading about each town in the guide book as I passed it.

I had read earlier about the Lake District, how it had been an inspiration to the Romantic poets. I was excited to see it, even though I never really appreciated the Romantic poets. I wondered if I’d be able to tell when we passed it. Then suddenly the flat pastoral scenery broke into hills unlike any I had seen before. They were green and grooved a flowing.

The Lake District (photo from wikipedia)

I was mesmerized. Then just as suddenly the Lake District ran away form me the clouds returned and the land changed to scraggy grass and heather. I had crossed into Scotland.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)